Chinese Sojourners

Chinese Sojourners

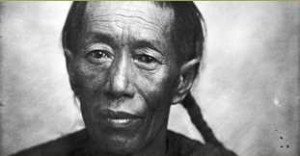

As the nineteenth century drew to a close, 11 percent of Portland’s residents were from China, and the city was home to the second-largest Chinese community on the West Coast. Many Chinese “sojourners” came to Portland to work in Oregon’s mines, on its railroads, and in canneries and construction; others built Portland’s seawall and underground infrastructure, constructing many of the urban systems we take for granted today; still others worked as servants, gardeners, cooks, and launderers.

As they worked hard to make the state a more civilized place to live, these early Chinese laborers faced severe discrimination and hardship, including being prevented by law from achieving citizenship and owning land. And that discrimination did not end in death: those who died in Portland were interred in a segregated part of Lone Fir Cemetery, technically designated “Block 14” and colloquially referred to as the “Chinese Burial Ground.” Chinese custom called for such burials to be temporary; the remains later to be disinterred and reunited with those of their ancestors across the Pacific Ocean. But for many of the Chinese sojourners who died in Portland, there was to be no reunion and their bones remained here in nameless graves, unremarked by the area they worked so hard to build.

As they worked hard to make the state a more civilized place to live, these early Chinese laborers faced severe discrimination and hardship, including being prevented by law from achieving citizenship and owning land. And that discrimination did not end in death: those who died in Portland were interred in a segregated part of Lone Fir Cemetery, technically designated “Block 14” and colloquially referred to as the “Chinese Burial Ground.” Chinese custom called for such burials to be temporary; the remains later to be disinterred and reunited with those of their ancestors across the Pacific Ocean. But for many of the Chinese sojourners who died in Portland, there was to be no reunion and their bones remained here in nameless graves, unremarked by the area they worked so hard to build.

Dr. Hawthorne and His Patients

Considered Oregon’s first psychiatrist, Dr. James C. Hawthorne founded the Oregon Hospital for the Insane in 1862 in what was then the city of East Portland. There he cared for more than five hundred people, offering compassionate therapy that was innovative for the time. Dr. Hawthorne was known for his humanity and his benevolence approach to medicine, and his empathic approach extended beyond the medical treatment of his patients. They had the opportunity to work in the fresh air, growing food and tending animals for the hospital’s use. By giving his patients a sense of purpose through such enterprises, Dr. Hawthorne fostered confidence and independence in a safe environment. The hospital received national recognition as one of the best and most progressive institutions in the United States.

Considered Oregon’s first psychiatrist, Dr. James C. Hawthorne founded the Oregon Hospital for the Insane in 1862 in what was then the city of East Portland. There he cared for more than five hundred people, offering compassionate therapy that was innovative for the time. Dr. Hawthorne was known for his humanity and his benevolence approach to medicine, and his empathic approach extended beyond the medical treatment of his patients. They had the opportunity to work in the fresh air, growing food and tending animals for the hospital’s use. By giving his patients a sense of purpose through such enterprises, Dr. Hawthorne fostered confidence and independence in a safe environment. The hospital received national recognition as one of the best and most progressive institutions in the United States.

When patients died who had been too poor to afford their own burial and whose bodies were not claimed by relatives, Dr. Hawthorne arranged for them to buried at Lone Fir, eventually paying out of his own pocket for the interment of about two hundred destitute patients. Such kindness was extraordinary at the time.